Continental Divide Trail spans 3,100 miles along the Rockies, and if you attempt it you should expect months of remote, high‑altitude terrain that demand serious planning; the route exposes you to storms, late snow, grizzlies and long stretches of limited water, yet rewards you with epic alpine views and a singular sense of accomplishment—most hikers take about six months and only 30–50% finish, so prepare your skills, gear, and resupplies accordingly.

Contents

- 1 Overview of the Continental Divide Trail

- 2 Pros and Cons of Hiking the Continental Divide Trail

- 3 Trail Statistics and Duration

- 4 Motivation for Hiking the CDT

- 5 Preparing for the Continental Divide Trail

- 6 Planning Your Hike

- 7 Who Should Attempt the Trail?

- 8 Highlights Along the Trail

- 9 Day and Section Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

- 10 Safety and Hazard Awareness

- 11 Trail Accessibility and Markings

- 12 Costs Associated with Hiking the CDT

- 13 Camping and Shelter Options

- 14 Additional Questions and Resources

- 15 The Continental Divide Trail Tested Me in Ways I Never Expected

- 16 Final Words

Key Takeaways:

- 3,100-mile, high-altitude thru-hike that typically takes ~6 months; weather and terrain make it one of the most demanding of the Triple Crown (completion ~30–50%).

- Logistics are a major challenge: long water gaps, sparse towns, and many resupplies require hitching or 4WD access—plan routes, caches, and daily mileage carefully.

- Extremely varied and remote scenery across Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico—spectacular but often solitary and best suited to experienced, fit backpackers.

Overview of the Continental Divide Trail

You’ll traverse the 3,100-mile backbone of the Rockies from Glacier National Park to the Mexican border, threading five states and moving through 25 National Forests, 21 Wilderness Areas, and 3 National Parks. Much of the route sits above tree line, typically takes about six months to thru-hike, and forces you to manage extreme weather, long gaps between water and resupply, and a completion rate near 30–50%.

What is the Continental Divide Trail?

The CDT is a continuous high-country route that follows the Continental Divide through Montana, Idaho, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico, offering multiple alternates and reroutes that change total mileage. You’ll hike alpine ridgelines, desert stretches, and remote valleys where resupplies often require hitches into town and water sources can be sparse or shared with livestock.

History of the Trail

Established in 1978 as the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail, the CDT was designated to protect and link existing trails and backcountry routes along the Divide. You’ll encounter sections that were formalized decades ago and others still shaped by route adjustments and land-management decisions.

Beyond its 1978 designation, the CDT evolved through collaboration between federal agencies, volunteers, and groups like the Continental Divide Trail Coalition, which helped place water caches and negotiate alternates. You’ll notice ongoing reroutes and added segments that reflect land access, wilderness designations, and decades of stewardship across vast, often remote public lands.

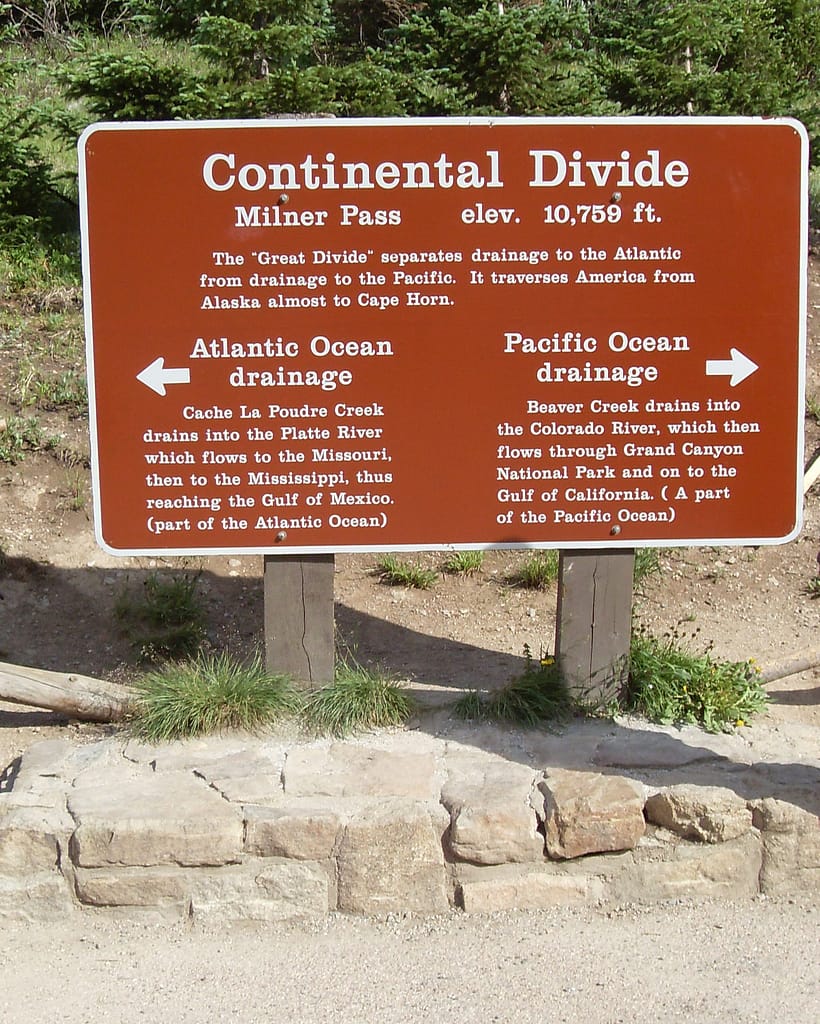

Significance of the Continental Divide

The Divide defines the hydrologic split where water flows either to the Pacific or the Atlantic/Gulf, shaping regional watersheds and the agricultural landscapes below. You’ll see how this geographic spine directs rivers, supports ranching on adjacent grasslands, and creates distinct ecological zones along the route.

Ecologically and recreationally, the Divide forms a continuous corridor for species like grizzly, moose, and mountain goat and concentrates climatic extremes—snowpack, wind, and aridity—along its length. You’ll face the tradeoffs: unparalleled wild scenery and wildlife encounters balanced against high-altitude exposure, water scarcity, and long stretches between towns and services.

Pros and Cons of Hiking the Continental Divide Trail

| Pros | Cons |

| Epic, continuous alpine scenery across 3,100 miles | Extreme remoteness; long stretches without services |

| Deep solitude and low crowds compared to AT/PCT | Low completion rate (~30–50%) |

| Access to 25 National Forests, 21 Wilderness Areas, 3 National Parks | Unreliable water sources and frequent dry ridgelines |

| Wildlife encounters—elk, moose, grizzly—offer unforgettable moments | Real wildlife risk (bear/grizzly encounters require protocol) |

| Numerous route alternates let you tailor difficulty | Route confusion and frequent reroutes add navigation burden |

| High reward: sense of Triple Crown accomplishment | Requires sustained ~20+ miles/day and months off work |

| Iconic highlights: Wind River Range, Grays Peak (14,278′) | Seasonal snow in MT/CO and late-spring/early-fall hazards |

| Fewer shelters means pure backcountry experience | Limited town access; many resupplies need hitches or 4WD |

| Community of experienced thru-hikers and targeted aid (e.g., NM caches) | Evacuation or injury can be complex and slow |

Benefits of Hiking the CDT

You gain unmatched mountainous variety over a roughly six‑month, 3,100‑mile journey: alpine ridgelines, the Wind River granite, San Juan passes, and desert‑high country in New Mexico. You’ll experience rare wildlife, minimal crowds, and the pride of completing one of the world’s toughest long‑distance routes—many hikers cite the Wind Rivers and Grays Peak (14,278′) as career highlights—while logging sustained endurance that translates to lasting outdoor skill and confidence.

Challenges and Drawbacks

You’ll face persistent logistical headaches: water scarcity that can stretch hours between reliable sources, resupplies requiring hitches or 4WD, frequent snow in Montana and Colorado, and real wildlife danger (I was charged by a grizzly 300 miles in). Expect to maintain ~20+ miles/day for months and accept that only ~30–50% of starters finish.

Detailed planning must cover worst‑case scenarios: Montana’s snow can linger into June and return in September, Elk Mountain and other climbs produce repeated false summits, and the San Juans hold late‑season snowfields. You’ll carry extra water or plan caches, learn bear‑aware techniques and bear canister use, and build contingency days for weather or injury. Resupply strategy often means mailing boxes to remote post offices or coordinating rides from sparsely spaced roads; a single missed hitch can cost days.

Balancing the Pros and Cons

You balance the CDT by matching objectives to preparation: if you want solitude and remote high country, accept longer daily miles, navigation complexity, and heavier contingency gear. Smart timing (northbound vs southbound), conservative mileage goals, and targeted training let you tilt odds toward finishing and enjoying the trail’s rewards without being overwhelmed by its hazards.

Practical tradeoffs reduce risk: start based on snowpack projections, pre‑ship resupplies to strategic towns, practice long back‑to‑back days in training, and plan alternates around technical sections. Learn to lighten pack weight where possible to offset water or bear canister mass, and establish evacuation plans with key towns and ranger contacts. Expect to trade some speed for safety and flexibility.

| Advantages | Mitigations / Drawbacks |

| Remote, pristine scenery | Carry satellite communicator; plan extra days for delays |

| Low crowding and solitude | Solo navigation skills required; consider buddy sections |

| High‑value highlights (Wind Rivers, San Juans) | Alternate routes if technical or snowy |

| Wildlife viewing | Use bear canisters; rehearse bear safety protocols |

| Flexible route with alternates | Frequent reroutes demand up‑to‑date maps and planning |

| Strong sense of accomplishment | Requires months off work and sustained physical fitness |

| Established aid (NM caches, resupply towns) | Caches are limited; plan for long dry stretches |

| Community knowledge and resources | Advice varies; verify with recent trail reports |

| Opportunity to tailor difficulty | Some alternates increase technical risk or length |

| Training benefits transferable to other expeditions | Injury or evacuation can be slow and costly |

Trail Statistics and Duration

How Long is the CDT?

At roughly 3,100 miles (4,989 km), the CDT runs from Glacier National Park to the Mexican border and pushes you into sustained, high-altitude terrain. Plan for a typical thru-hike of about six months; unpredictable snow, storms, and long gaps between water sources mean your timing and pace often determine whether you finish. Overall completion rates hover around 30–50%.

Breakdown of Miles by State

The trail segments read roughly: Montana ~575 miles, Idaho–Montana ~504 miles, Wyoming ~508 miles, Colorado ~722 miles, and New Mexico ~773 miles, so New Mexico and Colorado contain the longest continuous mileage you’ll plan for.

Montana’s 575 miles deliver the most remote backcountry and late-spring snow, while the Idaho–Montana border’s 504 miles force longer resupply hauls and 4WD access. Wyoming’s 508 miles include Yellowstone and the Wind Rivers—technical passes and route alternates—whereas Colorado’s 722 miles pack the highest sustained elevation (including Grays Peak). New Mexico’s 773 miles are the driest and hottest, with CDT Coalition water caches in the southernmost stretches to help you cross extended desert gaps.

Average Time to Complete

Most hikers budget about 5–7 months, with a common target near six months; that translates to roughly 15–20+ miles per day when accounting for zero days, resupplies, and slow terrain. Your start date, direction, and a snow year can shrink or stretch that window significantly.

Pace breaks down like this: finishing in ~180 days requires an average near 17 miles per day, while a faster five-month finish pushes you toward 20–25 miles daily. Expect zeros for rest or weather, slower mileage through technical alpine passes, and occasional forced delays from deep snow or river crossings—so build buffer days into your schedule and keep flexible logistics for town resupplies and hitching.

Motivation for Hiking the CDT

Personal Motivations

You sought the CDT after the AT and PCT to finish the Triple Crown and to test yourself on a 3,100-mile, high-altitude route that demands months of sustained effort. You crave purposeful isolation, long stretches between resupplies, and the raw moments—racing storms, a grizzly encounter, or running out of water—that force you to rely on planning, grit, and adaptability.

Common Reasons for Thru-Hiking

Many hikers tackle the CDT for challenge, solitude, and transformation: averaging 20+ miles a day over roughly 6 months becomes a crucible for physical and mental growth. You’re also drawn by the remoteness and wildlife, balanced against a sobering 30–50% finish rate that underscores how unforgiving high-altitude terrain and variable weather can be.

Specific motivations often map to sections: technical alpine routes in the Wind River Range tempt climbers, the long, dry stretches of New Mexico attract desert-savvy hikers, and the remote 575 miles of Montana appeal to those seeking true wilderness. You pick objectives—a fast finish, a scenic highlight like the Cirque of the Towers alternate, or simply learning to live lean on trail.

The Dream of the Divide

Walking the CDT means tracing the continent’s spine and witnessing watershed divides across 25 National Forests, 21 Wilderness Areas, and 3 National Parks, a dream for anyone wanting expansive, continuous mountain scenery. You envision long ridgelines, alpine lakes, and the satisfaction of moving along the backbone of America for thousands of miles.

That dream often crystallizes into concrete goals: standing on Grays Peak (14,278′), adding the 3-mile side trip to Mt. Elbert, spotting elk along the Gila River, or relying on CDT Coalition water caches in southern New Mexico—moments that make the hardships feel earned.

Preparing for the Continental Divide Trail

Plan for sustained effort over ~6 months, with sections where water sources can be dozens of miles apart, frequent weather swings, and limited towns; use route resources like the Explore the Trail page to map resupplies, alternates, and seasonal snowlines, then build a plan that nets you an average of 20+ miles a day and flexibility for storms, detours, and zero days.

Essential Gear and Equipment

Target a base weight of 15–20 lbs with a 50–65L pack for resupplies; bring a lightweight tent or tarp, 3-season sleeping quilt or bag rated to your coldest expected night, a reliable filter or purifier, and at least 2–4 liters of carrying capacity for dry sections. Add microspikes or crampons for spring/fall snow, and a bear-proof canister or strong food storage system in grizzly country.

Training and Fitness Preparation

Build to consistent 20+ mile days by doing long back-to-back hikes: aim for multiple weekends with 15–25 mile days carrying a 20–30 lb pack, and include sustained elevation gain training (1,500–3,000 ft/day) to simulate passes. Mix in hill repeats, stair workouts, and aerobic intervals to prepare lungs and legs for altitude and long mileage.

Follow a 10–12 week progressive plan: start with 3–4 hikes per week, add one long hike that increases 10% weekly, and include strength sessions (squats, deadlifts, lunges, core) twice weekly. Practice loaded descents to train knees, hydrate while hiking, and do at least one multi-day outing to test gear, food burn rate, and sore-point prevention.

Mental Preparation and Expectations

Anticipate long stretches of solitude, decision fatigue, and setbacks—only about 30–50% of starters finish—and plan coping strategies like micro-goals (mileposts, town treats), routines for bad-weather days, and contingency funds for unexpected transport or gear replacement. Expect storms, wildlife encounters, and long resupply gaps to test your judgement and patience.

Develop mental resilience with graded exposure: try solo overnight trips, practice making hard calls on route choices, and use journaling or habit anchors (morning checklist, evening stretching) to stabilize morale. Line up a support contact, schedule periodic calls, and accept that flexible pacing and planned zero days are part of long-term success.

Planning Your Hike

Plan for a 3,100-mile, high-altitude itinerary that typically takes ~six months and requires averaging 20+ miles a day to hit the snow window. Factor in long water and resupply gaps, frequent alternates, and limited cell service; many hikers carry buffer days for weather and route changes. Build a gear-to-food plan that balances endurance with weight—expect sections where you’ll be out of water or out of town for multiple days, and schedule maildrops or town re-supplies accordingly.

When Should You Start the CDT?

Northbound departures commonly begin in April while southbound starts cluster in June–July, driven by annual snowpack. Montana’s high passes often hold snow into late June and first snows return in September, so plan your timing to avoid deep snow or early-season storms. Direction affects logistics too: many hikers split 50/50 between N-to-S and S-to-N; pick the start that matches your tolerance for snow, heat, and town access.

Itinerary Planning and Resupply Points

Expect long stretches where towns are sparse and resupplies require a hitch or 4WD access; some sections can force resupply gaps of up to 150 miles. Maildrops to post offices or outfitters remain common, and you should plan to carry 3–7 days of food in remote sections, at roughly 1.2–2.0 lbs of food per day. Factor in buffer days for storms, river crossings, and alternates that add mileage.

Map out resupply cadence by section: shorter 4–7 day legs in Colorado and New Mexico where towns are closer, and longer 7–12+ day legs through Montana, Idaho borderlands, and parts of Wyoming. Use a spreadsheet with GPS coordinates, expected mileage, hitch difficulty, and post office hours. Pre-load maildrops with non-perishables and a lightweight stove fuel plan; keep a contingency stash in case a town is closed or you miss a hitch. Budget resupply weight to avoid burnout—each extra pound will amplify fatigue over 3,100 miles.

Combine smartphone mapping apps (downloaded offline), paper topo maps, and a compass. Carry GPX tracks but verify them in the field because the CDT has frequent alternates and reroutes; outdated tracks can send you off-route into dangerous terrain. Bring a satellite communicator (Garmin inReach or similar) for emergency check-ins where cell service is absent.

Download multiple map sources (Gaia GPS, FarOut/Guthook route packs, and USGS topo tiles) and store GPX files on a backup GPS device or a spare phone. Carry a 10,000–20,000 mAh power bank, and mark verified water waypoints and resupply GPS coordinates in advance. Check recent trail reports on forum groups and CDT Coalition updates before each section—those live notes often flag washed-out crossings, closed campgrounds, and newly placed water caches.

Who Should Attempt the Trail?

If you thrive on long, sustained hardship and solitude, the 3,100-mile CDT will reward you; plan to commit roughly six months, average 20+ miles/day, and accept that only about 30–50% of starters finish. You should be comfortable with long resupply gaps, limited cell service, and encounters with wildlife—my grizzly charge and water shortage at 300 miles are typical warnings of how remote and unforgiving the route can be.

Ideal Experience Levels

You’ll fare best if you have prior multi-day backpacking and route-finding experience—many successful CDT hikers have completed at least one long thru- or section-hike (AT, PCT, or a 500+ mile section). Nighttime solo camping, navigating off-trail, and past exposure to high-altitude terrain reduce risk and increase odds of finishing.

Physical Requirements

Expect sustained daily mileage and big elevation swings: plan on averaging 20+ miles/day, with routine day gains exceeding 3,000 ft and summit exposure above 14,278′ (Grays Peak). Pack weights commonly sit in the 25–35 lb range at resupply, while long dry stretches and steep, rocky terrain amplify physical demand.

Train specifically for repeated high-mileage days with elevation: include weekly long hikes of 20+ miles carrying your target pack, multiple consecutive back-to-back hiking days, and stair- or hill-repeat sessions to simulate sustained climbs. Strength work (deadlifts, lunges, core) cuts fatigue and injury risk; practice river crossings, load-bearing descents, and carrying 3–4 liters of water so you can handle water-scarce stretches. Acclimatize before high sections, pack a satellite communicator or PLB, and bring bear spray and a reliable water-filter—these items mitigate hazards from high-altitude storms, grizzlies, and remote breakdowns.

Assessing Personal Readiness

Gauge readiness by matching your skills to the trail’s demands: do you have time and funds for a six-month commitment, the tolerance for sustained solitude, and the ability to average 20+ miles/day? Comfort with self-rescue, basic gear repair, and independent resupply planning separates likely finishers from quitters.

Run concrete tests: complete a 7–14 day unsupported trip with full CDT gear, then a 100+ mile section relying on town resupplies and hitching. Log consecutive hiking days (4–6) with 20-mile efforts and 2,500–3,500+ ft gains to verify recovery. Drill navigation with map/compass and a GPS device, rehearse bear-spray deployment, and simulate contingencies (cold nights, lost food, storm bivies). If you can meet these performance metrics and stay mentally steady through multi-day discomfort, you have the practical readiness to start the CDT.

Highlights Along the Trail

You’ll traverse five distinct sections totaling roughly 3,100 miles, each with its own hazards and highlights: northern Montana’s granite wilderness, the Idaho–Montana spine into Yellowstone, Wyoming’s geysers and Wind Rivers, Colorado’s 14,000-foot peaks, and New Mexico’s high desert. Expect long resupply gaps, high-altitude weather, and variable trail conditions; planning your start, alternates, and water strategy around those realities will determine whether you finish in ~six months or bail early.

Montana: “M” as in Most Remote

Across ~575 miles in Montana you’ll face late snow (often into June) and early snows by September, massive passes, and stretches where you might go hours without water. You’ll negotiate granite peaks in places like the Bob Marshall Wilderness and Glacier National Park, and encounters with moose or grizzly are real risks—so you carry bear spray, plan larger resupplies, and keep daily mileage conservative to avoid getting pinned by weather.

Idaho-Montana border: Truly Wild

The ~504-mile border section delivers alpine lakes, endless forest, and long climbs like Elk Mountain’s relentless ascent; many trailheads require a 4WD or long hitch, making resupply logistics a primary concern. You’ll earn every view here, but expect hot, exposed approaches and false summits that sap your miles and water fast.

Resupply strategy dominates this segment: plan 50–100 mile food carries where necessary or line up friends/contacts with a 4WD shuttle. Elk Mountain’s approach can cost you 3–6 hours of hard climbing; cool early starts and filtering every source you pass will keep you moving. Navigation through dense timber and talus fields can cost extra time—factor slower daily averages into your schedule.

Wyoming: From Mountains to Plains

Wyoming’s ~508 miles begin with Yellowstone’s backcountry—geysers, hot springs, and thermal features away from crowds—then push through the Tetons and Wind River Range where alternates like Cirque of the Towers or Knapsack Col put you among granite spires and glacial basins. Expect variable terrain: thermal hazards, alpine traverses, and the odd long, flat stretch across the Great Divide Basin.

Objective hazards increase in the Wind Rivers: afternoon thunderstorms, loose rock, and steep talus require you to pick travel windows carefully. If you take technical alternates, plan for route-finding challenges and potential snowfields into July. Logistics-wise, towns are sparse—resupply timing and vehicle access will shape your daily goals.

Colorado: The Spine Along the Divide

Colorado’s ~722 miles concentrate the classic CDT experience: continuous mountains, high passes, and peak-bagging opportunities like Grays Peak at 14,278′ and a common 3-mile detour to Mt. Elbert. The San Juans cap the state with stunning alpine lakes and late-season snow that can force slow travel or detours, so you’ll plan start dates to minimize post-holing.

Altitude becomes the dominant factor: sustained elevations above 10,000–12,000 feet mean thinner air and faster fatigue, so pace yourself and expect lower daily mileage. Afternoon storms are common—start before dawn to avoid lightning exposure on exposed ridgelines. If you want a fast Colorado push, map water sources precisely and aim for 20+ mile days when terrain allows.

New Mexico: From Desert to Mountains

New Mexico’s ~773 miles are the driest and often the hottest section; the Continental Divide Trail Coalition places water caches in the south to bridge long dry stretches. You’ll cross the Gila River, encounter elk in the north, and encounter Border Patrol activity and barbed-wire fences near the final 150 miles, so plan town stops and exit strategies accordingly.

Water planning here is mission-critical: heat can spike into the 90s, and distances between reliable springs may exceed 20–30 miles in places—carry extra capacity and check cache statuses before leaving town. Nights can still be cold at altitude, so balance weight against safety; conservative pacing and midday shade breaks will keep you from blowing up in the desert heat.

Day and Section Hikes on the Continental Divide Trail

Mix of day hikes and multiday sections let you sample the CDT without committing months; high elevation, unpredictable weather, and long water stretches mean you should pick routes with reliable access. For planning, resupply points, and maps consult the Continental Divide Trail Coalition’s route resources. Popular single-day favorites include Glacier basins, Wind River circuits, and San Juan traverses.

Glacier National Park

In Glacier National Park, you can claim a day on the CDT by hiking sections near the border—Highline and Piegan Pass offer dramatic glacial cirques and 360° views. You will encounter steep talus, lingering snow into July, and increased grizzly activity, so carry bear spray and time your approach for lower wildlife movement. Permit rules and busy trailheads make early starts and weekday plans advisable.

Bob Marshall Wilderness

The Bob Marshall Wilderness rewards section hikers with vast, roadless country and limited human contact; expect long approaches, braided trails, and challenging navigation across ridgelines. You can stitch together 3–7 day segments, but pack for limited resupply and high bear density, and rely on maps and a GPS—cell service is effectively nil.

Bob Marshall spans over 1 million acres of alpine valleys and dense forest; CDT stretches there routinely demand 10–20 mile days between trailheads and cross poorly marked junctions. Aim for July–August when most snow recedes, yet anticipate afternoon storms and variable creek crossings. Carry detailed topo maps, a compass or GPS, and an emergency satellite communicator—search-and-rescue response times can be hours to days in this country.

Wind River Range

In the Wind River Range you can sample classic CDT alternates like the Cirque of the Towers or Knapsack Col; granite spires, glacial lakes, and high passes make day trips spectacular but expose you to afternoon lightning and steep talus. Many routes cross 12,000–13,000-foot terrain, so plan for altitude and careful route-finding.

Wind River contains Wyoming’s high ground, including Gannett Peak at 13,809′, and the CDT skirts basins fed by persistent glaciers. Some alternates require crossing permanent snowfields where crampons or a rope may be helpful early in the season. Expect rapid weather swings, rockfall, and afternoon thunderstorms; schedule high-pass travel for mornings and carry glacier-aware gear if you’ll take technical lines.

San Juan Mountains

The San Juans deliver steep, wild CDT miles with sweeping meadows and alpine lakes; late-season snow and loose, rocky passes make route choices consequential. You can build 2–6 day loops that showcase intense scenery, but verify water sources and town access before you head out—resupply gaps are real.

San Juans include sustained high-elevation stretches with multiple passes above 12,000′; the region also sees the North American Monsoon in July–August, producing heavy afternoon storms and lightning. Towns such as Silverton and Ouray serve common alternates for resupply, yet many hikers still mail packages to small post offices—plan logistics well and avoid mid-day summit pushes during monsoon season.

Safety and Hazard Awareness

How Dangerous is the CDT?

You should expect a high-risk, low-probability environment: remote terrain, long resupply gaps, and high altitude combine to produce most incidents. Common causes of rescue calls are storms, river crossings, falls, dehydration, and hypothermia; many hikers drop out for injury or weather delays. About 30–50% of starters don’t finish, and proper navigation, first aid training, and conservative decision-making materially reduce your odds of needing rescue.

Wildlife Encounters and Precautions

Expect moose, elk, black bears, and grizzlies—Montana and the northern ranges are highest risk (I was charged by a grizzly). Carry and practice deploying bear spray, store food in a certified bear canister where required, make noise in dense brush, and avoid calves and rutting bulls. If a large predator approaches, back away slowly; for an aggressive grizzly, deploy spray at ~20–30 feet and stand your ground if charged.

Go deeper: choose a 7.9–9.7 oz bear spray in a hip holster and practice removing the safety tab so you can deploy under stress. In grizzly country, use a bear canister and stash food >100 feet from camp, downwind if possible; in treeless desert sections, secure food in vehicles or odor-proof sacks inside canisters. Give moose and elk at least 50 yards, avoid calves, and log aggressive sightings with rangers to trigger local advisories.

Weather and Environmental Hazards

Afternoon thunderstorms, lightning above treeline, sudden snow, and flash floods are the main weather threats; above 10,000–12,000 ft storms can form within minutes and snow lingers into summer in northern sections. Nighttime temps often drop below freezing, increasing hypothermia risk, while spring melt can turn streams into dangerous crossings. Plan alternates and water caches to manage these variables.

Adopt conservative timing and gear: start before dawn to avoid afternoon lightning, carry a waterproof shell, insulating midlayer, and a sleeping bag suited to alpine nights. Pack microspikes or crampons and an ice axe for spring snow in the Wind Rivers and San Juans, and expect the most hazardous river crossings in May–June. Use mountain-forecast.com/NOAA for planning and load GPX alternates to detour to lower-elevation routes when ridgelines become unsafe.

Trail Accessibility and Markings

Access along the CDT ranges from paved trailheads with town services to remote 4WD-only approaches and multi-day backcountry stretches; you’ll cross 25 National Forests, 21 Wilderness Areas, and 3 National Parks, so plan for long hitch rides and occasional road closures. Expect sparse services in Montana and New Mexico’s high desert, and choose start dates to avoid late-spring snow or early fall storms that can strand you for days.

Trail Conditions and Maintenance

Conditions change rapidly by state: Colorado sections receive more regular trailwork and signage, while Montana’s 575 miles and parts of Wyoming see limited maintenance and lingering snow into June. Federal agencies and volunteers do most upkeep, but reroutes and washouts happen frequently; carry topo maps, updated CDT Coalition cues, and factor in unpredictable creek crossings and eroded tread into daily mileage estimates.

How Well Marked is the CDT?

Markings are highly inconsistent—some segments have blazed trails, signs, and cairns, while others are largely unmarked boot-paths or route-finder alternates; you should rely on GPX tracks (FarOut/Guthook), paper maps, and a compass. In populated states the route is much easier to follow, but in remote stretches you’ll need to navigate by map and satellite coordinates.

For example, Glacier National Park and many Colorado corridors feature clear signage, whereas the Idaho–Montana border and Wind River alternates often require reading topography and following cairn sequences. The Continental Divide Trail Coalition publishes regular route notes and GPX updates—download recent files, print critical maps, and save offline waypoints for water sources and trail intersections to avoid costly route-finding delays.

Off-trail travel on the CDT includes snowfields, bushwhacks, class 2–3 scrambles, and unsigned alternates; you may face hours of cross-country travel between obvious tread and water, so sharpen route-finding skills and carry a reliable GPS device. Anticipate afternoon storms, whiteout snow, and steep talus that can force slow, technical travel and burn extra time from your schedule.

Practical tactics: practice compass bearings and pacing on training hikes, cache 1–2 days of extra food when aiming for alternates, and mark bailout roads in advance. Use satellite messengers for emergency extraction, set conservative mileage targets on complex sections, and study notes from recent thru-hikers—an off-season report can save you hours and keep you off dangerous snow-covered ridgelines.

Costs Associated with Hiking the CDT

Estimated Budget for a Thru-Hike

Plan on roughly $5,000–$8,000 for a full CDT thru-hike. Typical breakdown: food/resupplies $2,000–$3,000 (≈$12–$18/day over ~150–180 days), initial gear $1,500–$3,500, travel/shuttles/hostels $500–$1,000, permits/fees and incidentals $300–$1,000. Factor in replacement items (shoes, electronics) that can add $300–$800 mid-hike, especially after long, remote stretches where water scarcity or storms force detours.

Permits and Fees

No single CDT permit covers the entire trail; you’ll need multiple backcountry permits and park passes. National Parks and some Wilderness Areas require backcountry permits or entrance fees (often <$30 per permit), while many USFS/BLM sections use free registration or self-issue systems. Failing to secure permits can result in fines or being turned away, so check each managing agency for rules before you plan resupplies or alternates.

Some high-use areas enforce quotas and advance reservations—plan to apply weeks to months ahead for places like Glacier or popular alternates in the Wind River Range. Expect to arrange 3–8 permits over a thru-hike and carry proof (printed or digital). Day-use fees, vehicle permits for trailheads, and paid CDT Coalition services (water caches, maps) add to the total, so track dates and receipts closely.

Gear Investments

Expect initial gear costs of about $1,500–$3,500 for a lightweight, durable kit: backpack $200–$400, shelter/quilt $300–$600, sleeping bag/quilt $200–$500, sleeping pad $80–$200, stove/filter $50–$200, footwear $150–$300, electronics/power $100–$300. Quality choices save weight and miles but raise upfront costs; factor in extras like gaiters, crampons or microspikes for late snow.

On the CDT you’ll replace consumables (boots every ~400–500 miles—so 2–3 pairs), which can add $300–$900. Water filters vary: Sawyer Mini ≈$25 vs pump filters ~$150; bear spray is recommended in grizzly country (~$40–$70). Test gear on multi-day trips, carry repair kits, and budget for unexpected gear failures after heavy river crossings or rock scrapes.

Camping and Shelter Options

Expect to mix developed campgrounds with dispersed backcountry camping across the CDT’s 25 National Forests, 21 Wilderness Areas, and 3 National Parks. Developed sites concentrate near towns and trailheads and often provide toilets, potable water seasonally, and bear boxes; most high-country miles offer no shelters, so you carry a tent, tarp, or bivy. Permit and group-size limits apply in many Wilderness and Park zones. Afternoon thunderstorms, high winds, and altitude exposure make site choice and shelter selection mission-critical for your safety and sleep.

Campgrounds and Designated Sites

Developed campgrounds at trailheads and towns supply vault toilets, potable water (seasonal), picnic tables, and sometimes showers; fees typically run $5–$25 per night, and reservation availability varies. Reliable town options include Bozeman, Helena, Salida, Silverton, and Taos, though accessing some requires a hitch or 4WD. Use designated sites to refuel, top off water, and avoid long campsite searches after a 20+ mile push. In busy months, plan reservations or expect limited space.

Techniques for Wild Camping

Choose sites at least 200 feet (about 70 steps) from water on durable surfaces or established sites; avoid fragile alpine tundra and wet meadows. Pitch on level ground below exposed ridgelines to reduce lightning and wind exposure, and stake wisely in rocky or snowy terrain. In grizzly country, carry a bear-resistant canister or execute a practiced bear hang (pack >10–15 feet off the ground and 4 feet from the trunk). You’ll trade weight for safety—pack accordingly.

For bear hangs, bring a 50–60 ft cord and rehearse the counterbalance or Moki method before remote use; aim for a limb ~15 ft high so your pack sits >10–15 ft up and 4 ft out from the trunk. Coordinate water caches in arid stretches with the Continental Divide Trail Coalitio,n where available, and mark cache GPS points. When melting snow, budget stove fuel—melting 1 liter can take roughly 6–12 minutes, meaning extra fuel needs impact your resupply plan.

Leave No Trace Principles

Follow the seven Leave No Trace principles: plan ahead, travel on durable surfaces, dispose of waste properly, leave what you find, minimize campfire impacts, respect wildlife, and be considerate of others. Dig a cathole 6–8 inches deep and at least 200 feet from water, trails, and campsites for human waste where allowed; pack out toilet paper and hygiene products. Fires are frequently prohibited above tree line or in dry southern sections—carry a stove and avoid burning driftwood or living wood.

Verify Wilderness- and Park-specific rules before each section: parts of the Wind River Range and some Colorado basins may require human-waste pack-outs or wag bags during peak season—complying prevents citations and long-term damage. Strain greywater and scatter it widely at least 200 feet from water after washing a short distance from camp; if a site shows erosion or vegetation loss, move to an established campsite to reduce cumulative impact across the 3,100-mile route.

Additional Questions and Resources

You can dial in permits, resupplies, and hazard planning before you leave: expect to average 20+ miles a day on a thru-hike, plan for water scarcity in long desert stretches, and keep bear-aware gear where grizzlies roam. Many hikers finish in 5–6 months and the historical completion rate sits around 30–50%, so stack prep, up-to-date route data, and contingency plans into your itinerary.

FAQs about the CDT

Backcountry permits are required for overnight stays in many National Parks and designated Wilderness Areas, so verify park-specific rules before a section. Expect resupply intervals of roughly 4–7 days in most places and plan start dates around snow windows (northbound April, southbound June–July typical). Watch for high‑altitude snow, river crossings, and large carnivores; carry bear spray and know how to use it.

Recommended Reading and Guides

Start with the Continental Divide Trail Coalition’s resources for official maps and water reports, pair those with a reliable mobile app like FarOut (formerly Guthook) for waypoint navigation, and use topographic apps such as Gaia GPS or USGS topo downloads for offline backup. Guidebooks and printed maps help when cell service fails.

Buy or download the CDT Coalition GPX/routes pack and load it into FarOut or Gaia for turn-by-turn waypoints and alternate routes; print crucial topo pages or a compact map set for each state as a paper fail-safe. Pay special attention to guidebook notes on alternates, stream reliability, and vehicle-accessed resupply points—many hikers staple a laminated waypoint sheet to their map case.

Online Resources and Communities

Use the Continental Divide Trail Coalition site for official updates, consult Trail Journals and active Facebook groups for recent trip reports, and scan the CDT subreddit or dedicated forums for planning threads. Community-maintained water reports and resupply spreadsheets are invaluable for short-notice changes and local intel.

Before a section, read recent Trail Journals entries for that segment (dates and mileages shown), post a shakedown or shuttle request in Facebook groups to arrange town pickups, and download the community water spreadsheet to your phone—then update it when you find dry springs or new caches so other hikers benefit from your on-trail intel.

The Continental Divide Trail Tested Me in Ways I Never Expected

When the Trail Became the Teacher

Three hundred miles in, you learn fast: after racing storms and a grizzly charge, that last sip of water before a three-hour dry ridgeline turns your afternoon into survival math. You averaged 20+ miles a day, yet a single missed spring forced a 4-hour hitch for resupply. The CDT compresses stats—4,989 km of exposure and 30–50% completion rates—into daily choices you make on tired legs, reshaping how you plan, push, and accept limits.

Final Words

So the Continental Divide Trail will test your planning, endurance, and judgment across remote mountains and high deserts; you should prepare for long waterless stretches, variable weather, and sparse resupplies, because with proper preparation you’ll earn unmatched solitude, spectacular alpine vistas, and the satisfaction of completing one of America’s most demanding long-distance hikes.